INTRODUCTION

Thymic neoplasms originate from the epithelial cells of the thymic tissue. They commonly occur in the anterior mediastinum, however, they can arise from an aberrant or remnant thymus. Ectopic thymic cervical neoplasm is rare. Therefore, patients with neck masses are often misdiagnosed as having other diseases (e.g., thyroid neoplasm or lymphatic neoplasm) on the initial imaging study, fine needle aspiration cytology, and frozen section at the time of surgery. This report presents a rare case of ectopic thymic squamous cell carcinoma that was misdiagnosed as thyroid carcinoma. In addition, we review other studies to determine the characteristics of ectopic thymic carcinomas. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication.

CASE REPORT

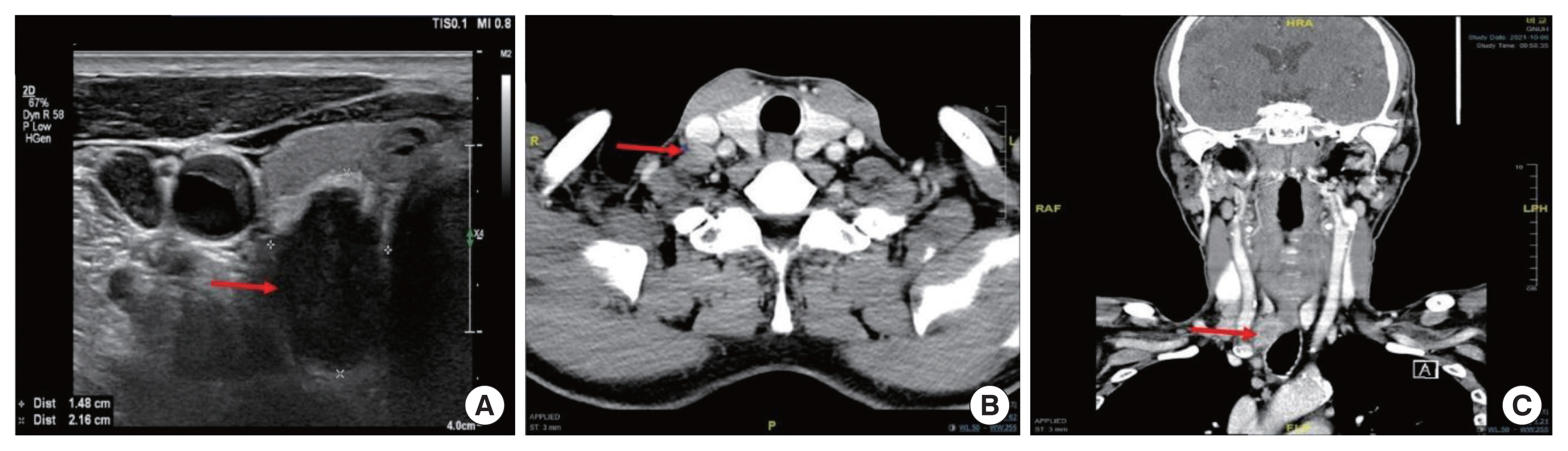

A 65-year-old man presented with neck bulging, which had recently rapidly increased in size and was accompanied by hoarseness that lasted approximately 2 months. Thyroid function and calcitonin levels were within normal limits. Ultrasonography imaging showed multiple thyroid masses, including a 2.5 cm hypoechoic nonparallel-shaped nodule in the right inferior thyroid (Fig. 1A). Computed tomography scan imaging showed enhancing mass which was abutment with the esophagus in the posteroinferior side of the right thyroid (Fig. 1B and C). There were multiple enlarged lymph nodes (LNs) in the right supraclavicular area and the upper mediastinum. Fine needle aspiration cytology of the mass confirmed malignancy, however, it was difficult to classify them into specific types. The possibility of poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma was suspected.

Surgery was performed shortly after. Intraoperatively, the tumor and surrounding LNs were locally advanced, with adhesion to posterior wall of trachea and esophagus. The right recurrent laryngeal nerve was invaded by the metastatic LNs and had to be sacrificed. The left thyroid gland and the recurrent laryngeal nerve were freed. Total thyroidectomy was performed with bilateral central neck LN dissection and right lateral neck LN dissection were performed. In the removed specimen, the tumor size was about 2.8 cm, and the margin was unclear with the surrounding tissues. The result of the frozen biopsy on operation time was revealed the possibility of malignancy with uncertain papillary features. The patient recovered well and was discharged 5 days after the operation. The final histologic examination revealed that squamous thymic carcinoma (Fig. 2A and B) with 15 metastatic LNs metastases (10 at central LNs and 5 right lateral LNs). Immunohistochemistry was negative for CD5 (Fig. 2C) and positive for CD117 (Fig. 2D) and thyroid transcription factor-1.

Postoperative positron emission tomography-computed tomography showed postoperative nonspecific inflammatory changes in the thyroid bed area and faint FDG uptake in the mid-esophagus (mean SUVmax). The endoscopic biopsy results of esophagus also showed malignancy, which was similar to that of the previous operative thyroid specimens.

The patient recommended palliative chemotherapy after multidisciplinary clinic, but he and his families decided to refuse chemotherapy. So, he underwent only palliative radiotherapy (1,540 cGy/7 fractions and sequentially 5,000 cGy/25 fractions) in the thyroid bed, neck LN and anterior mediastinum. The patient was followed for 12 months after surgery and showing no signs of disease progression.

DISCUSSION

Thymomas and thymic carcinomas originate from the epithelial cells of the thymus within the anterior mediastinum, and ectopic thymomas account for only 4% of all thymomas [1]. Ectopic thymomas result from migration, failure of descent, hypoplasia, or dislocation and can be found in the extra-mediastinal regions such as the neck, pulmonary hilum, thyroid, lung, pleura, or pericardium. In contrast to mediastinal thymomas, ectopic cervical thymomas are usually left-side dominant, middle-aged, female individuals (female to male ratio, 7:1), type A or AB World Health Organization (WHO) histologic classification, and have fewer associations with myasthenia gravis and lower invasiveness [2–4].

Diagnosis of ectopic thymoma is difficult because there are no definitive diagnostic methods. Fine needle aspiration cytology is usually performed to establish a neck mass. The microscopic features of ectopic thymomas are similar to those of mediastinal thymomas. However, due to its rare incidence and unusual locations, it is difficult to interpret the cytological features of a palpable mass in ectopic cervical thymoma. Thymomas are composed of varying proportions of neoplastic epithelial and reactive lymphoid tissue. Although the epithelial and lymphocytic components are not evident after cytology, diagnosing of thymoma is more difficult [5].

Thymic carcinomas represent heterogenous group of tumors exhibiting more aggressive malignant behavior compared than thymomas. According to WHO criteria for histologic classification, thymic carcinomas consist of over 10 subtypes. Thymic squamous cell carcinoma is major type of thymic carcinoma (61.8%–73.4% of thymic carcinoma) [6,7], and is often accompanied by desmoplastic to sclerohyaline stroma. And it should be excluded from invasion from adjacent pulmonary carcinoma of metastasis. They showed positive immunostaining for CD5, KIT (CD117), FOXN1, and/ or CD205, and assay of the KIT mutation assay may be helpful to identify potential therapeutic targets [7]. The ectopic thymic carcinomas are extremely rare. We reviewed the characteristics of eight previously published case reports written in English (Table 1) [8–15]. Except for one case (case 3), all others were male individuals, and the mean age was 58 years old. The immunoexpression of CD117 and CD5 in the tumor cells further supports thymic origin. CD117 expression is detected in approximately 80% of thymic carcinomas, whereas that of CD5 is detected in 70%. Undifferentiated thymic carcinomas can be negative for CD5 or CD117 [7].

Because ectopic thymic carcinoma is very rare, little is known about its prognosis. In a recent study from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database analysis [9], thymic squamous cell carcinoma was frequently diagnosed in older patients with advanced-stage disease. However, it has a more favorable survival rate than other subtypes of thymic carcinomas. Complete resection is an important prognostic factor, and the Masaoka-Koga stage and chemotherapy strongly affect prognosis.

Herein, we report a rare case of ectopic thymic squamous carcinoma. Accurate diagnosis of ectopic thymic carcinoma is challenging because of its scarcity with unusual location and varying histopathological characteristics. Clinicians and pathologists should be aware of this condition.