ABSTRACTThere have been several reports of complications of small bowel lymphoma, such as bleeding, obstruction, and perforation, often require emergency surgery. It is hardly showed complications of bleeding and wound dehiscence for diffuse large B cell lymphoma with distal ileum involvement, which needed urgent surgery and medical management. A 65-year-old man with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with distal ileum involvement experienced both intestinal bleeding and perforation during the course of treatment. As the patient was diagnosed with stage III disease, resection before chemotherapy was not considered due to the resulting delay in chemotherapy, which necessitated sufficient tissue healing. Chemotherapy is important when treating small bowel lymphoma, complications such as bleeding and perforation should always be considered for the treatment of small bowel lymphoma, and surgery is necessary in this situation. After surgery of the small bowel, subsequent chemotherapy could cause wound dehiscence and perforation; therefore, adequate recovery time should be given before chemotherapy.

INTRODUCTIONThe gastrointestinal tract is the most common extranodal site involved in non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) [1]. Gastrointestinal lymphoma is usually secondary to widespread nodal disease. Although lymphoma can arise from any region of the gastrointestinal tract, the most commonly involved sites in terms of its occurrence are the stomach, small intestine, and ileocecal region. Histopathologically, almost 90% of primary gastrointestinal lymphomas are of B-cell lineage, with very few T-cell lymphomas and Hodgkin lymphoma [2].

For more advanced or systemic intestinal NHL, in stages III–IV, there is no definitive evidence regarding the treatment strategy [3]. Chemotherapy is beneficial, but the role of surgery is difficult to assess [4]. There is a systemic review that emergency surgery was required at disease presentation for between 11% and 64% of intestinal NHL cases. Perforation occurs in 1% to 25% of cases and occurs during chemotherapy for NHL. Intestinal bleeding occurs in 2% to 22% of cases. Obstruction occurs more commonly in the small bowel (5%–39%) than in large bowel NHL [4].

Herein, we report a case of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with distal ileum involvement that experienced both intestinal hemorrhage and perforation during the course of treatment.

CASE REPORTThis case report was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Bucheon St. Mary’s Hospital (IRB No. HC21ZASI0020), and informed consent was obtained from the patient.

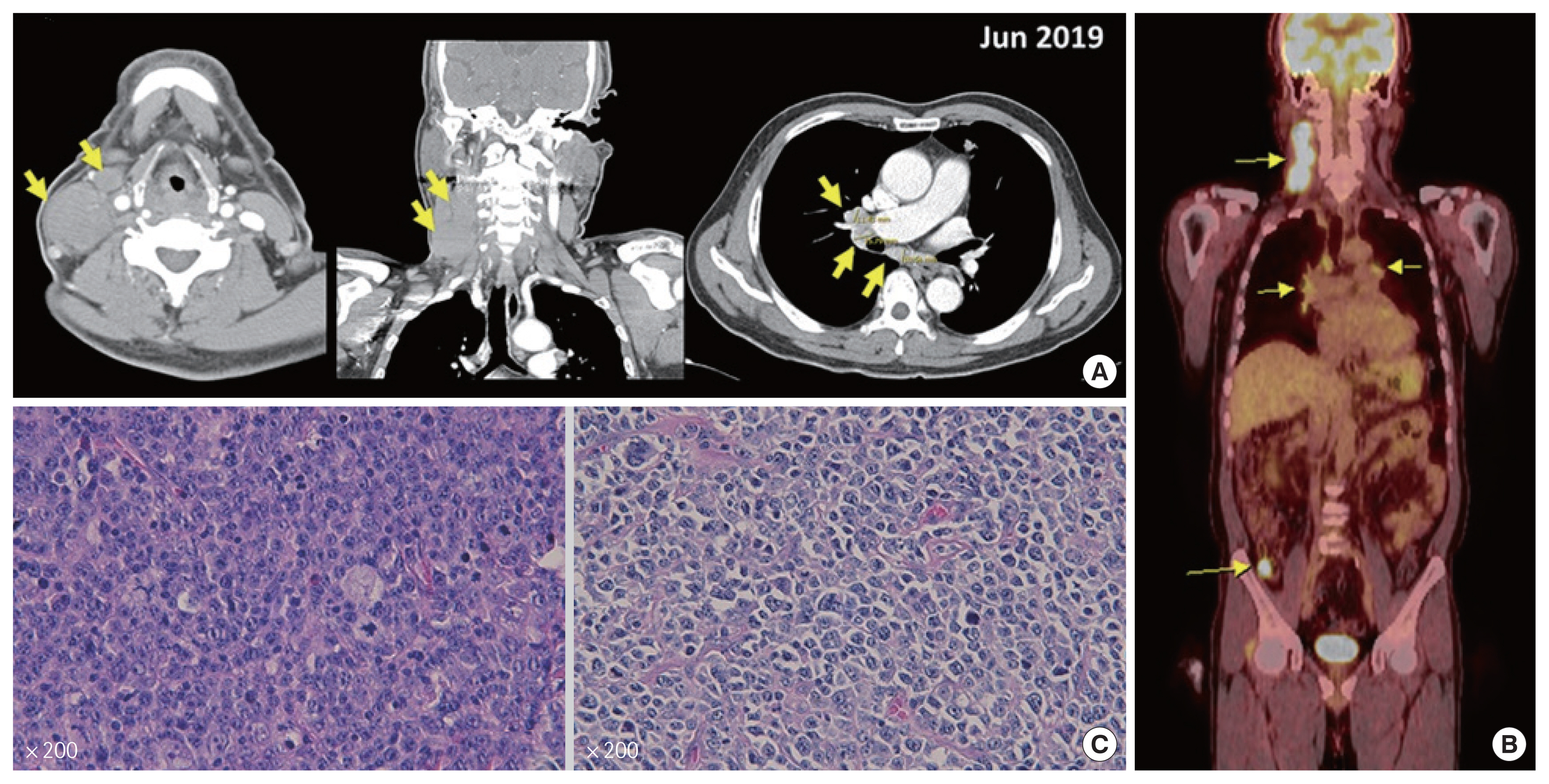

A 65-year-old man was referred to our hospital with right and neck mass for 1 month. The patient had a history of hypertension and an old cerebral infarct with medication. There were no specific findings on the patient’s laboratory findings. Findings on neck and chest computed tomography (CT) showed multiple enlarged homogeneous enhancing lymph nodes in the right neck, right supraclavicular, right upper, lower paratracheal, subcarinal, right hilar, and interlobar areas (Fig. 1A). Positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) scan showed fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid uptake in the right, neck, right, supraclavicular area, mediastinum, portocaval, both axillar, and distal ileum (Fig. 1B). An excisional biopsy of the right level II neck node was performed. Immunohistochemical staining results were positive for BCL2, CD20, MUM1, and Ki-67 at 70%. This was consistent with malignant lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and activated B cell type (Fig. 1C).

For workup of lymphoma, we conducted bone marrow biopsy, and the result was normocellular bone marrow with no evidence of lymphoma involvement. The patient was diagnosed with stage III diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by Ann Arbor staging. He was treated with six cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine, and prednisone). After six cycles of chemotherapy, the involved lymph nodes regressed, but there was remnant focal FDG uptake in the distal ileum (Fig. 2A). However, the patient had no symptoms, such as abdominal pain or hematochezia. Abdominal CT scan showed no definite wall thickening in the distal ileum. Therefore, the patient was examined again by a CT scan 3 months later. Abdominal CT showed eccentric wall thickening in the distal ileum with homogeneous enhancement, suspicious of recurrent lymphoma. The PET scan showed aggravation of intense focal FDG uptake in the distal ileum (maximum standard uptake value, from 31 to 48) (Fig. 2B). The patient was treated with two cycles of DL-ICE (dexamethasone, L-asparaginase, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide) every 3 weeks. Seven days after the start of 2nd cycle of chemotherapy, the patient visited the emergency room for hematochezia. His vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 130/80 mmHg; pulse rate, 100/min; respiration rate, 20/min; body temperature, 36.5°C. The hemoglobin level decreased to 11.0 g/dL. Abdominal CT scan and duodenoscopy/colonoscopy were performed. Abdominal CT showed improvement in wall thickening of the distal ileum (Fig. 3A). Endoscopically, there was fresh blood in the colon, but no definite bleeding focus was found (Fig. 3B). As bloody stool persists and hemoglobin level was decreased from 11.0 to 8.5 g/dL, he was underwent angiography. However, there was no active bleeding on mesenteric angiography. The patient underwent emergency surgery for ongoing bleeding. Segmental resection of the ileum was performed, and there was a mass with ulceration in the distal ileum (Fig. 3C). The pathology result was malignant lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, activated B cell type consistent with initial neck biopsy. After surgery, hematochezia was stopped, and the patient was discharged.

After 5 weeks of small bowel surgery, the patient recovered, and he maintained a normal diet. He was treated with 3rd cycle of DL-ICE. Eight days after 3rd cycle of chemotherapy, the patient complained of sudden abdominal pain. The patient’s white blood cell count was 1,190/μL and the absolute neutrophil count was 240/μL. Abdominal CT scan revealed leakage at the distal ileoileal anastomosis site with scanty pneumoperitoneum (Fig. 4A). He received conservative treatments, such as nil per os, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, and antibiotic therapy. After 1 week, an abdominal CT scan was performed, which showed about 6 cm-sized fluid collections in the right lower quadrant area (Fig. 4B). Pig tail drainage was performed for these fluids, and there was no documented growth of microorganisms. After several days, the patient did not experience abdominal pain and had a diet. The pigtail catheter was removed, and the patient was discharged. We decided to stop the chemotherapy because there was no definite recurred lesion and concerning about complications such as leakage, dehiscence and perforation of bowel. He is now visiting an outpatient clinic with a follow-up response evaluation.

DISCUSSIONThis is a case that showed complications of bleeding and wound dehiscence for small bowel lymphoma, which required urgent surgery and conservative management.

There have been many reports of complications associated with small bowel lymphoma. There have been several case reports on the treatment of bleeding caused by small bowel lymphoma. Rodriguez-Lago et al. [5] reported the case of a 53-year-old male patient who presented with gastrointestinal bleeding caused by primary small bowel lymphoma. The patient underwent laparoscopic small bowel resection of the proximal jejunum and was diagnosed with B-cell follicular lymphoma. Kroner et al. [6] reported the case of a 32-year-old man presenting with hematemesis due to primary small-bowel diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. After transfusion of blood products, the patient received R-CHOP chemotherapy. The patient tolerated the chemotherapy, and a PET scan after six cycles of chemotherapy revealed a complete response to treatment. In our case, after the 2nd cycle of DL-ICE chemotherapy, the patient complained of hematochezia, and small bowel bleeding was suspected, and emergency surgery was performed due to ongoing bleeding and hemodynamic instability. After recovery from small bowel surgery, the patient received 3rd cycle DL-ICE chemotherapy. However, he was placed in a second emergency for bowel leakage and abscesses. Fortunately, the patient recovered with conservative treatment.

Perforation through small bowel lymphoma is a serious complication with a high mortality rate [7]. The occurrence of perforations leads to considerable morbidity from sepsis, multiorgan failure, prolonged hospitalization, complications of wound healing, delays in the initiation of chemotherapy, and mortality [8].

Several studies have reported inferior outcomes of gastrointestinal lymphomas when complicated by perforation [3,9]. In one study from a single center, between 1975 and 2012, 9% of patients (92/1,062) developed a perforation, of which 55% (51/92) occurred after chemotherapy. The median day of perforation after initiation of chemotherapy was 46 days (mean, 83 days; range, 2–298 days), and 44% of perforations occurred within the first 4 weeks of treatment. At the time of the last follow-up, 60% (55/92) of the patients with perforation died. Of these, 30% (28/92) died directly due to perforation or subsequent complications [8]. In another study, 17 of 59 patients had perforation during treatment of primary small intestinal lymphoma and underwent emergency surgery. At the time of the last follow-up, 12 of the 17 patients had died, and the study revealed that perforation often leads to significantly dismal results [10].

In one retrospective cohort study that compared the treatment strategies for patients with intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, the 3-year overall survival rate was 91% in the surgery plus chemotherapy group and 62% in the chemotherapy-alone group (P<0.001). Surgical resection followed by chemotherapy may be an effective treatment strategy for localized intestinal lymphoma [11].

For aggressive or multifocal disease, resection before chemotherapy may not be technically feasible or advisable because of the extent and location of the disease, as well as the resulting delay in chemotherapy necessitated to allow sufficient tissue healing. In a systemic review of 28 studies of primary gastrointestinal NHL, definitive statements regarding its survival benefit remain limited due to lack of patient stratification based on timing and indication for surgery, and survival outcomes were not typically stratified by emergent versus elective surgery [12]. The decision to resect a gastrointestinal lymphoma before chemotherapy depends on several factors, including the location and extent of the disease, the pace of the disease, the presence of hemorrhage, and whether resection would result in long-term complications such as short-gut syndrome [8].

As shown in this case, complications such as bleeding and perforation should always be kept in mind for treatment of small bowel lymphoma. Although the principal treatment for advanced lymphoma is systemic chemotherapy, surgery is necessary for the complications of small intestinal lymphoma. After surgery of the small bowel, subsequent chemotherapy could cause wound dehiscence and perforation; therefore, adequate recovery time should be given before chemotherapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSConceptualization and design: SRK, SHC, JYJ, GJL. Investigation: SRK, TGG, HL, MSJ, GJL. Writing - original draft: MSJ, GJL. Writing - review and editing: SRK, SHC, JYJ, TGG, HL, MSJ, GJL.

REFERENCES1. Olszewska-Szopa M, Wrobel T. Gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Adv Clin Exp Med 2019;28:1119-24.

2. Ghimire P, Wu GY, Zhu L. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:697-707.

3. Kako S, Oshima K, Sato M, Terasako K, Okuda S, Nakasone H, et al. Clinical outcome in patients with small-intestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2009;50:1618-24.

4. Abbott S, Nikolousis E, Badger I. Intestinal lymphoma: a review of the management of emergency presentations to the general surgeon. Int J Colorectal Dis 2015;30:151-7.

5. Rodriguez-Lago I, Carretero C, Munoz-Navas M. Gastrointestinal bleeding caused by primary small bowel lymphoma in a patient who received a renal transplant. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:e2.

6. Kroner PT, Mankal PK, Elhaddad A, Shi W, Abed J, Paik IJ, et al. Primary small-bowel diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting as hematemesis. Endoscopy 2015;47(Suppl 1 UCTN):E526-8.

7. Chao TC, Chao HH, Jan YY, Chen MF. Perforation through small bowel malignant tumors. J Gastrointest Surg 2005;9:430-5.

8. Vaidya R, Habermann TM, Donohue JH, Ristow KM, Maurer MJ, Macon WR, et al. Bowel perforation in intestinal lymphoma: incidence and clinical features. Ann Oncol 2013;24:2439-43.

9. Gou HF, Zang J, Jiang M, Yang Y, Cao D, Chen XC. Clinical prognostic analysis of 116 patients with primary intestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Med Oncol 2012;29:227-34.

10. Xu J, Lu W, Shen Z, Ji F, Li Y, Zhang H. Diagnosis and treatment for primary small intestinal lymphoma of 59 cases: a follow-up study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2016;31:1377-9.

Fig. 1Radiological and histological features of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. (A) Initial neck and chest computed tomography showed multiple enlarged lymph nodes. Arrows indicate target lesions. (B) Initial positron emission tomography-computed tomography scan image. Arrow indicates target lesions. (C) Morphology and pathologic findings of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (H&E, ×200).

Fig. 2Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan images. (A) The PET-CT scan image after six cycles of chemotherapy showed recurred status. (B) The PET-CT scan showed aggravation of intense focal fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in distal ileum. Arrow indicates target lesions.

Fig. 3Comparison of abdominal computed tomography scans and endoscopic images before and after treatment. (A) Abdomen computed tomography scan showed improvement of wall thickening of distal ileum. (B) Endoscopically image showed fresh blood in the colon. (C) Surgical specimen of ileum was sighted with mass with ulceration in distal ileum.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||